You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘behavioral economics’ tag.

Paul Krugman: How Economists Got It VERY Wrong

By Shlomo Maital

Paul Samuelson was arguably the great economist of the 20th C., and certainly one of the greatest of all time. He was a professor at MIT, where I taught for 20 summers, and invariably could be found on weekends working away in his office, even after officially retiring. His book Foundations of Economic Analysis (1947) (his Ph.D. thesis) reconstructed economic theory, using clever mathematics. But Samuelson was not deceived by his keen mathematical skill. “Elegance is for tailors”, he once said, in describing elegant, but empty, economic theories.

Alas the Economics profession did not heed him. UK Economist Geoffrey Hodgson reminds us of Paul Krugman’s 2009 New York Times article, analysing where economists went wrong in missing the 2007-8 financial collapse, and in some ways actually causing it with their gung-ho free market enthusiasm.

At that time, Krugman (a Nobel Prize winner, it should be recalled) wrote:

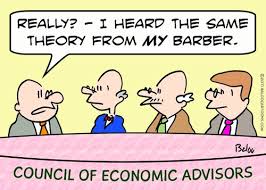

“As I see it, the economics profession went astray because economists, as a group, mistook beauty, clad in impressive-looking mathematics, for truth. Until the Great Depression, most economists clung to a vision of capitalism as a perfect or nearly perfect system. That vision wasn’t sustainable in the face of mass unemployment, but as memories of the Depression faded, economists fell back in love with the old, idealized vision of an economy in which rational individuals interact in perfect markets, this time gussied up with fancy equations.” …..the central cause of the profession’s failure was the desire for an all-encompassing, intellectually elegant approach that also gave economists a chance to show off their mathematical prowess. ”

I feel a personal sense of loss and defeat as I read those words. I chose by mistake to study economics. I never did have the mathematical ability to excel in research. But I did have an insight, that behaviour was more important than math, in understanding how people choose and decide. But that idea was like aging wine, ‘before its time’. Behavioral economics has now replaced math as mainstream, helped by the tailwind of economics’ massive failure in 2007/8.

Will this help economists avoid culpability in the next financial crisis?

Economists Finally See The Light!

By Shlomo Maital

With my new Ph.D. in Economics, in 1967, I quickly knew I was in the wrong discipline. My wife, a psychologist, helped me see that the basic assumptions economists made about human beings were ridiculous. As Nobel Laureate Daniel McFadden summarized them: “sovereign in tastes, steely-eyed and point-on in perception of risk, and relentless in maximization of happiness.” I also knew WHY economists assumed a world that did not exist. Without these assumptions, they could not build mathematical theorems about behavior. So the tail of math wagged the dog of reality. With my wife, I did some research applying psychology to economics, 41 years ago, in 1972, long before behavioral economics became fashionable (it was published only in 1978)* I also wrote a book on the subject, in 1982, but 31 years ago, no-one was interested. **

Today one can say that the mainstream of economics is behavioral. In a new paper by McFadden***, “he outlines a “new science of pleasure”, in which he argues that economics should draw much more heavily on fields such as psychology, neuroscience and anthropology. He wants economists to accept that evidence from other disciplines does not just explain those bits of behavior that do not fit the standard models. Rather, what economists consider anomalous is the norm. Homo economicus, not his fallible counterpart, is the oddity. “ (Source: The Economist, April 27, 2013).

Almost none of the models and assumptions of conventional economics hold water in the face of behavioral research. For example: in microeconomics, more choice is always better than (or at least as good as) less choice. As The Economist notes: “Economists tend to think that more choice is good. Yet people with many options sometimes fail to make any choice at all: think of workers who prefer their employers to put them by “default” into pension plans at preset contribution rates. Explicitly modeling the process of making a choice might prompt economists to take a more ambiguous view of an abundance of choices. It might also make them more skeptical of “revealed preference”, the idea that a person’s valuation of different options can be deduced from his actions. This is undoubtedly messier than standard economics. So is real life.”

And if conventional microeconomics, macroeconomics is completely out to lunch. Chief IMF economist Olivier Blanchard recently described macroeconomics as a “cat in a tree” – treed by the global financial crisis, unable to say decisively whether austerity (budget cutting) is good or bad or indifferent.

The behavioral revolution in economics came a bit too late. If it had come a decade earlier, if it had focused on key variables like trust and risk perception, perhaps economics could have helped forestall the global financial collapse in 2008, rather than contribute to it.

* Sharone Maital and Shlomo Maital, “Time preference, delay of gratification and the intergenerational transmission of economic inequality”. In Orley Ashenfelter and Wallace Oates, editors, Essays in Labor Market Analysis, (Halsted Press/John Wiley & Sons, New York: 1978, 179-199).

** Shlomo Maital, Minds, Markets and Money: Psychological Foundations of Economic Behavior, Basic Books: New York, 1982, x + 310 pages. (hardcover and paperback).

*** * D. McFadden “The New Science of Pleasure”, NBER Working Paper No. 18687, February 2013