You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘biology’ tag.

Global Chaos: Is Snails-Pace Evolution to Blame?

By Shlomo Maital

Evolution is an ongoing nonstop race against an ever-changing world. But it appears to be too slow to be helpful lately. Global chaos? The pace of social and technological change outraces the ability of evolution to deal with it well.

This is my conclusion from a new study * from the University of Michigan.

- The Neutral Theory of Molecular Evolution. Jianzi Zhang et al. Nature Ecology and Evolution. 2025.

“For decades, many evolutionary biologists have believed that most genetic changes shaping genes and proteins are neutral. Under this view, mutations are usually neither helpful nor harmful, allowing them to spread quietly without being strongly favored or rejected by natural selection. A new study from the University of Michigan challenges that long-standing assumption and suggests evolution may work very differently than once thought.

“As species evolve, random genetic mutations arise. Some of these mutations become fixed, meaning they spread until every individual in a population carries the change. The Neutral Theory of Molecular Evolution argues that most mutations that reach this stage are neutral. Harmful mutations are quickly eliminated, while helpful ones are assumed to be extremely rare, explains evolutionary biologist Jianzhi Zhang.”

“Zhang and his colleagues set out to test whether this idea holds up when examined more closely. Their results pointed to a major problem. The researchers found that beneficial mutations occur far more often than the Neutral Theory allows. At the same time, they observed that the overall rate at which mutations become fixed in populations is much lower than would be expected if so many helpful mutations were taking hold.”

But beneficial mutations often don’t last! Why? A mutation that provides an advantage in one setting may become harmful once conditions shift, the researchers note.

There are lots of terrific ‘idea mutations’ emerging all over the world. But they are not numerous enough, powerful enough, and full-blown enough, to help much with the global chaos we face. The pace of change is outstripping the pace of evolutionary progress.

Example: Democracy is a social ‘mutation’. Dates back to Greece, 2,500 years ago, but it has evolved nicely. Ooops…capitalism, too, a mutation, generates billionaires. They buy political influence and push political systems to the autocratic right. Harmful evolutionary mutation. Solution? Regulate, tax, etc.? Too slow.

What should be done? Let’s help Nature. Let’s foster creativity, and use artificial intelligence as a full collaborator to generate powerful mutative solutions to global chaos and global crises.

Evolution has created us humans and our intelligence. Can we speed it up, to bail us out? It’s worth a try!

Replaceable You! Virtual You!

By Shlomo Maital

Virtual You: How Building Your Digital Twin Will Revolutionize Medicine and Change Your Life. Peter Coveney, Roger Highfield, Venki Ramakrishnan. 2023 Princeton University Press

Replaceable You: Adventures in Human Anatomy. Mary Roach. Random House, 2025.

One of my never-miss podcasts is Ira Flatow’s Science Friday. This week two wonderful books were reviewed: Virtual You, and Replaceable You. Virtual You reviews how creating a digital copy of each person’s bodily mechanisms and organisms (each of us has a bodily organism unlike any other) can advance medicine by light years, at a time when identical drugs are prescribed for everyone, even though we are all different. This is particularly true of women, at a time when most clinical trials are done on white males. Personalized medicine has been long discussed; digital twin technology may make it feasible and cost-effective. “… your digital twin can help predict your risk of disease, participate in virtual drug trials, shed light on the diet and lifestyle changes that are best for you, and help identify therapies to enhance your well-being and extend your lifespan”, write the authors.

Replaceable You is about the spare parts business – how we are replacing hearts, lungs, livers, knees, hips, eye lenses, and hair follicles, among others, with ‘spare parts’. This too is revolutionizing medicine. It is also a source of heartache, literally – many people wait in long queues for, e.g., kidney transplants. One approach the author describes is the ‘body shop’ approach — hearts for transplant have to be used within four to six hours of removal from the dead donor, and many such hearts are not up to par and are not usable. Scientists look for ways to ‘repair’ defective hearts, and to prolong the time after which they become unusable, to expand the supply – currently, with huge excess demand and long queues.

Science Friday this week discusses how AI has shown promise in speeding development of new drugs – but so far has failed. The current model of drug development, involving mice (very poor representations of human anatomy) and then people (long, expensive, and often misleading) is costly and cumbersome. It was hoped that AI could analyze billions of molecules, to find the right one to block a ‘bad protein’ that causes illness. But so far – it has not happened.

One of the fascinating frontiers of research for ‘spare parts’ is 3D biological printing of organs – corpuscles, cells, etc. This is incredibly complex. But – one day, perhaps, a 3D printer will be able to print a heart – perhaps using key cells from one’s own body to forestall immune rejection.

Mapping every human cell

By Shlomo Maital

Two important developments in cell biology, published this week, suggest major breakthroughs in how healthcare is provided.

- Preventing disease is always superior to treating it, though Big Pharma loves selling billion dollar drugs. One approach to this has been through use of CAR-T cells.

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy is a way to get immune cells called T cells (a type of white blood cell) to fight cancer by changing them in the lab so they can find and destroy cancer cells. Up to now, this approach has been used by modifying the cancer patient’s own cells. Published work by Chinese researchers, joined by Americans, suggests that donor CAR-T cells can be used as well. This is hugely important – because modifying each cancer patient’s CAR-T cells is expensive and takes time. Using modified donor cells means that large stocks of CAR-T cells can be placed ‘on the shelf’ – though it is unclear whether Big Pharma would be willing to cut down the branch their huge profits rests on.

2. Writing in The Economist, Geoffrey Carr explains how the Human Atlas Project may also change our lives.

“One thing that is now being done is the Human Cell Atlas, a project made possible by the Human Genome Project’s identification of the 20,000 or so protein-coding genes that can determine a cell’s nature. And what a thing it is. The endeavour has involved thousands of researchers spread over all six inhabited continents proposing to track down every type of cell in the body, where each is located, what their jobs are, how they form in a developing embryo, how they collaborate, how they cause diseases when they go wrong and so on.

“The long-term goal is to create something akin to a human digital twin—or, rather, a whole series of twins covering the spectrum of human sexes, ages and geographical backgrounds that can be poked and prodded digitally to see how they react. This will help researchers understand how actual bodies behave, decide which experiments are worth doing in the real world and, perhaps, provoke ideas that might not otherwise have had their lightbulb moment.

It is a huge endeavour, dwarfing the HGP in size and scope, but cleverly keeping costs down by piggybacking on and co-ordinating the efforts of people already working in established laboratories, rather than starting (as many genome-project efforts did) from scratch. Like the genome project, though, it makes its data available immediately, for any and all to use.

“However, unlike the genome project, which was frequently in the news up until that triumphant announcement at the White House in June 2000, the Human Cell Atlas has stayed largely under the radar. As we reported almost two years ago, the contrast is partly a result of the genome project having had well-run PR, a clear end goal, a competitor in the form of a private venture which aimed to beat the public one, and the (ahem) rather large egos of some of those involved (on both the public and private sides).”

= = = = =

It’s pretty simple. Our 20,000 genes (some of them) lead to expression of proteins. Proteins run our lives, keep us well and fight invading germs. Mapping our 30 trillion cells in the human body (!), linking proteins to cells, is an enormous project, requiring global cooperation among cell biologists. But it can yield huge benefits in preventive medicine.

The atlases that showed detailed geographies enabled seafarers to explore the world, and they changed our world. An atlas of the cells in the human body may do the same, for our preventive medicine.

The Secret of Life: 3 Proteins

By Shlomo Maital

Have you ever wondered: How in the world do those little sperms – cells with big heads and wriggly tails – manage to get into the ovum, the female cell produced by the ovaries? Cells have thick walls. They have to – otherwise, really bad stuff could get int. COVID, for instance, gets into cells, because it has a huge long spike, a spear, and it pokes its way into the cell, and ‘persuades’ the cells in our body to produce copies of itself. But the little sperm? They have no spike.

But what DO they have? Writing in the New York Times, October 17, Elizabeth Preston explains clearly and movingly a new finding, that solves the mystery.[1]

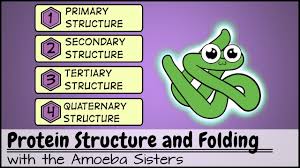

A Google company, DeepMind, developed software, AlphaFold, whose principal developers shared the Nobel Prize this year for chemistry – a rare event in which the Nobel for science is given to a group of researchers from a business, rather than to scholars from a university or lab. Using AlphaFold, scientists at a research institute in Vienna have discovered the nature and structure of the three key proteins in the head of the sperm, that act as ‘keys’ to combine with a protein in the ovum cell wall and ‘unlock’ it, to enter, fertilize it – and generate a zygote, a fertilized ovum ready to reproduce. Proteins are driven by genes, and they control our lives. They have very complex ‘folded’ structures that are really hard to decipher — until now.

And – here’s the clincher. Those 3 proteins – they are shared by a huge variety of living things – humans, yes, and ….zebrafish. Those lovely striped black and white fish. Same 3 proteins on their testes (sex organs).

Does this make you think, that we humans are not really at the head of the food chain, but instead, PART of an amazing ecosystem with which we living things share many things, including those key (double meaning) proteins? Does this make you feel a bit humble, as it does me?

Picture that obstreperous sperm, outracing a million rivals, reaching the ovum, knocking politely on the door – no answer. Knocks again. No answer. Whips out the keys (3 proteins), turns the key in the lock, wriggles inside – and creates a new life, or the start of it. And then? Those two helixes of interlocked DNA, they separate, one stays, the other moves on to the divided cell… and the process continues.

There is incredible beauty in the creation of life – and those 3 proteins have unlocked only a very tiny part of it.

[1] Elizabeth Preston. “Sperm can’t unlock an egg without the ancient molecular key”. NYT Oct. 17.

Nobel 2024: Take Chances

By Shlomo Maital

Alfred Nobel

The Nobel Prizes 2024 for physics, chemistry and medicine have been awarded. Here they are:

Physics: John Hopfield, “for foundational discoveries and inventions that enable machine learning with artificial neural networks”, Geoffrey Hinton“for foundational discoveries and inventions that enable machine learning with artificial neural networks;

Chemistry: David Baker, “for computational protein design”, Demis Hassabis “for protein structure prediction”

Medicine: Victor Ambros, “for the discovery of microRNA and its role in post-transcriptional gene regulation”; Gary Ruvkun, “for the discovery of microRNA and its role in post-transcriptional gene regulation”

There is a rare link. AI was a key tool used to discover the structure of proteins (the secret of life, and how DNA impacts our lives), and indirectly to help decipher microRNA. And another link. The winning scientists mostly left their comfort zones, to venture into new and risky fields, simply because they were curious. And they did so mainly against the best advice of the ‘experts’.

Take calculated risks, as General George Patton urged, before he did so in World War II and saved the Allies from the German Battle of the Bulge.

Good advice.