You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Federer’ tag.

Life Lessons from Roger Federer

By Shlomo Maital

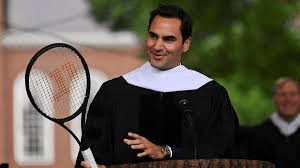

On June 9, 2024, a year ago, tennis great Roger Federer gave the commencement address at Dartmouth University, an Ivy League school. Rustin Dodd recently wrote about it in The New York Times. Federer’s address has become viral, like the late Steve Jobs’ commencement address in 2005 at Stanford.

“Now, I have a question for you,” Federer said, looking out across a sea of umbrellas at the commencement ceremony for Dartmouth College. “What percentage of points do you think I won in those [career] matches?” (He played a total of 1,526 singles matches during his career. He won 1,251 of those matches).

Federer won 80% of his 1,526 matches.

He paused.

“Only 54 percent,” he said.

It was one of those statistics that at first seemed incorrect. Federer was one of the most dominant athletic forces of this century. That guy lost nearly half of his points? He won 80% of his matches and only won 54% of his points? ?????

“When you lose every second point, on average, you learn not to dwell on every shot,” he told the crowd. “You teach yourself to think, ‘OK, I double-faulted. It’s only a point.’ When you’re playing a point, it has to be the most important thing in the world, and it is. But when it’s behind you, it’s behind you. This mindset is really crucial, because it frees you to fully commit to the next point and the next point after that, with intensity, clarity and focus.”

I think this is a powerful lesson. Bad things happen to everybody. At times, our brains insist on replaying them, There is value in learning from failure. But – only to a point.

Federer explains that past failures should be time-dated, like prescription drugs. Figure out what can be learned. And move on. Focus.

Federer appears to have practiced his own version of a psychotherapy technique known as focusing, developed by Eugene Gendlin. It is “a quality of engaged accepting attention”, a kind of focused mindfulness about where we are at this present moment, with past memories, troubles, worries, anxieties, etc., distilled out of our thoughts.

Think about the wonderful women’s final at Rolain Gros, the French tennis championship. American Coco Gauff vs. world #1 Sabalenka. Here is one account:

“Sabalenka overpowered the American in the early stages, breaking her serve to love amidst a run of nine unanswered points, while Gauff looked spooked, spraying misses to all parts of the court. But suddenly an inspired drop shot, a Sabalenka double-fault and a flashing forehand winner brought up a break point which Gauff converted. Sabalenka was now rattled and let a push from Gauff drift past her, thinking it was going long only for it to bounce four inches inside the baseline, as the second seed levelled the set at 4-4. It was a jaw-dropping mistake from a player who had gone 4-1 up against defending champion Iga Swiatek in her semi-final and let that lead slip.”

Sabalenka later explained that she indeed became unsettled. My hunch is she let those past mistakes dwell in her mind, and lost what Federer had in his career: Extreme focus. In contrast, Gauff appears to have mastered it, at least for this match.

The expression “water under the bridge” expresses the idea that what’s past, is past. Can we emulate Federer? We’re not pro tennis players – but we are all in the complex game of life, where focus is essential.

The world is in a huge mess. Let that not keep you from seeing the incredible beauty of Nature, and beauty of the human spirit, all around us, every minute.

Tell Yourself (White) Lies

By Shlomo Maital

I was lucky to watch on TV one of tennis’s all-time great matches, while at a conference in Switzerland. In the Wimbledon final, Novak Djokovic (Serbia) beat Roger Federer (Switzerland) in 5 long sets – longest final match in Wimbledon history. The final set went to a 12-12 tie, and, by the rules, to a tie-breaker, which Djokovic won 7-3. The match lasted nearly 5 hours!

The crowd was one-sidedly cheering for the 37-year-old Federer, even (rudely) at times cheering Djokovic’s misses and flubs.

Later, Djokovic explained how he overcame the psychological disadvantage of having the crowd nearly unanimously against him.

I pretended they were cheering for me, not for him, he explained.

What? Tell yourself a bald lie? Fool yourself? Deceive yourself?

Well, why not! When you’re in a tight spot, or even when you’re not, it is entirely allowed, and even desirable, to tell yourself white lies – narratives that pull you through.

For instance — you’re on a long flight, scrunched into an Economy seat, nearly no leg room – and the ADHD 10-year-old behind you is slamming your seat back incessantly, playing a video game on the touch screen. For three hours. And he just won’t stop.

The white lie? “this is good for me. I’m learning resilience, endurance, patience. I’m learning from suffering. It will come in handy one day.”

Try it. Tell yourself a white lie. Try hard to believe it.

And if people say, stop kidding yourself! Ask them, innocently:

Why?

Learning from Federer: Just Go For It

By Shlomo Maital

At the ripe old age of 36, Roger Federer has again won Wimbledon. Not only that – he won it without losing a single set — a feat last done decades ago by Bjorn Borg.

What’s his secret? He’s happy to reveal it. From his teens, he says he was careful to take care of his body. Fitness, eating right…. Pro tennis puts enormous strain on the body, and it has to be given tender loving care except when you’re on the court, when the start-stop violence rips ligaments, tendons, muscles and everything else.

This year, Federer was careful to ration the events in which he competed, pacing himself and his body. He may well regain his #1 position this year.

But Chris Clarey, who covers tennis for the New York Times, reveals another Federer secret. Federer plays it safe when it is wise to do so, regarding fitness, scheduling, and lifestyle. But on court? He’s a risk-taker.

“I wish we’d see more players and coaches taking chances at net [i.e., rushing to the net, and volleying], because good things happen at net, but you have to spend time up there to feel confident up there,” Federer said. At Wimbledon, Federer did ‘serve and volley’ (serve and then rush to the net) 16% of his service points – in other words one serve in six – and that doesn’t seem like much, but in fact it is more than double the 7% tournament average (i.e. servers rush the net one time out of every 14 serves].

A key point here is: You have to serve and volley a lot, to get good at it. And you might lose points initially as a result. But – take risks, stick to it – and you will win.

Now, I admit – Federer has totally out-of-this-world eye-hand coordination. And this is vital at the net. But his wisdom applies to us in life. Practice taking calculated risks, as General George S. Patton once said, especially when everyone else is playing it safe. Over time, you get better at it. Nothing ventured, nothing gained.

Wawrinka and Samuel Beckett: On Failure

By Shlomo Maital

Samuel Beckett Stan Wawrinka

There is a very interesting connnection between Swiss tennis star Stan Wawrinka, #3 in the world and winner of the Australian Open, and author and playwright Samuel Beckett, Irish-French, author of Waiting for Godot.

Wawrinka just won the Australian Open Grand Slam, unexpectedly defeating Rafael Nadal, to whom he had repeatedly (at least 12 times in Grand Slam events) lost in the past. His win was decisive, in four sets, and Wawrinka at times (according to the New York Times) bullied Nadal, something that Nadal usually does himself with fierce ground strokes and serves.

Wawrinka himself found it hard to believe; and it is rare that a number 8 ranked player wins over the Big Four (Murray, Federer, Djokovic, Nadal).

What is his secret? According to Greg Bishop (Global New York Times, Jan. 28), last March Wawrinka had the following words, written by Beckett, tattooed on his left forearm: “Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better!” (from his play Westward Ho!, 1983).

Before Sunday’s Australian Open final, the Big Four players had won 34 of the 35 major titles. That means, if you’re not one of the big four, you have a one in 35 chance to win, or less than three per cent. But, if you try to fail better (that means, try your absolute best, facing huge odds, battle with everything you have, leave it all on the court, and walk off with dignity and pride even if you lose), one day you will win. Or, you will “fail to fail”, as Bishop puts it nicely, which means you will succeed.

Wawrinka offers us a big lesson in life. And it was fun to see how he himself could hardly believe he had won.