You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘coronavirus’ tag.

COVID-19: Calibrate Your Risk Perception

By Shlomo Maital

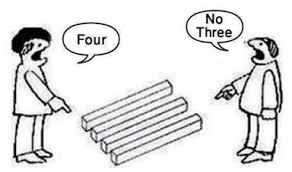

How risky is COVID-19 to me, personally? How do I process the news, numbers, fake news, and hysteria, to evaluate the seriousness of the threat to me, personally?

Behavioral economics knows a lot about risk perception. Many years ago, Kahneman and Tversky showed, with simple this-or-that choice experiments, that we humans overwhelmingly overestimate small probabilities.

This seems to be the case with COVID-19. Writing in the New York Times, medical doctor and psychiatrist Richard Friedman observes: *

Throughout the country, people are stockpiling food in anticipation of a shortage or a quarantine. Supplies of Purell hand sanitizer flew off the shelves in local pharmacies and are now hard to find or even unavailable online. I understand the impulse to secure one’s safety in the face of a threat. But the fact is that if I increase the supply of medication for my patients, I could well deprive other patients of needed medication, so I reluctantly declined those requests. As a psychiatrist, I frequently tell my patients that their anxieties and fears are out of proportion to reality, something that is often true and comforting for them to realize. But when the object of fear is a looming pandemic, all bets are off.

Friedman continues:

In this case, there is reason for alarm. The coronavirus is an uncertain and unpredictable danger. This really grabs our attention, because we have been hard-wired by evolution to respond aggressively to new threats. After all, it’s safer to overact to the unknown than to do too little. Unfortunately, that means we tend to overestimate the risk of novel dangers. I can cite you statistics until I am blue in the face demonstrating that your risk of dying from the coronavirus is minuscule compared with your risk of dying from everyday threats, but I doubt you’ll be reassured. For example, 169,000 Americans died by accident and 648,000 died of heart disease in 2017, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. As of Sunday morning 19 Americans had died from the coronavirus.

OK – so what SHOULD we be doing, then, in the face of panic that the objective risk does not justify?

Find ways to help and reassure others, notes the wise Dr. Friedman.

Researchers found that when subjects made selfish decisions, the brain’s reward center was activated, whereas when they made generous decisions, a region of the brain implicated in empathy lit up. This suggests that people are more likely to be altruistic if they are primed to think of others and to imagine how their behavior might benefit them.

The good news is that even in the face of fear, we do have the capacity to act in ways that would help limit contagion during an epidemic. Specifically, we can behave altruistically, which benefits everyone. For example, research shows that when people are told that it is possible — but not certain — that going to work while sick would infect a co-worker, people are less willing to stay home than when they are reminded of the certainty that going to work sick would expose vulnerable co-workers to a serious chance of illness. Stressing the certainty of risk, in other words, more effectively motivates altruism than stressing the possibility of harm The lesson for the real world is that health officials should be explicit in telling the public that selfish responses to an epidemic, such as going to work while sick or failing to wash your hands, threaten the health of the community.

And what should our great leaders do?

Specifically, public figures need to convey loudly and clearly that we should not go to work or travel when we’re sick and that we should not hoard food and medical supplies beyond our current need — not just give us health statistics or advise about how to wash our hands.

Let us all try to recalibrate our risk perceptions. COVID-19 will spread, it will afflict a lot of people, it IS NOT possible to put it back in Pandora’s box. But there are a lot of other scary things going on in this world that threaten each of us. Because we have known them for a long time (ordinary flu, traffic deaths, etc.), we are habituated. COVID-19 is new, scary and rather unknown. We will in time come to know it. We will overcome it. And in the meantime, help and reassure your family and your friends. Take it from Dr. Friedman.

* “The Best Response to the Coronavirus? Altruism, Not Panic. The impulse to secure your safety is understandable but counterproductive.” by Dr. Richard A. Friedman, NYT March 8/2020

The COVID-19 Crisis: How to Save Your Business and Protect Your Family

By Shlomo Maital

Israel’s national airline, El Al, just announced it is laying off 800 workers. That is a huge number. Many believe that El Al was in trouble well before the COVID-19 crisis and is just using it as an excuse to shed excess workers.

True or not – we are about to see a wave of layoffs, all over the world, in airlines, hotels, cruise ships and many other industries suffering from a parts shortage.

An article published on Feb. 27 in Harvard Business Review is timely. “Lead your business through the coronavirus crisis”, by Martin Reeves, Nikolaus Lang and Philipp Carlsson-Szlezak, of BCG Boston Consulting Group.

Here are 12 things the authors suggest that you do.

- Update intelligence. That is track the latest information. This is harder than it seems, because there is an enormous amount of hysteria, panic and false data. 2. Beware of hype. See #1 – “as you absorb the latest news, think critically about the source of the information before acting on it.” 3. Share information. “We have found that creating and widely sharing a regularly updated summary of facts and implications is invaluable”. 4. Use experts and forecasts carefully. “Each epidemic is unpredictable and unique, and we are still learning about the critical features of the current one.” 5. Reframe your understanding of what’s happening constnatly. “A Chinese general once said: Issue orders in the morning, change them in the evening”. 6. Beware of bureaucracy. Everybody will weigh in, about what to do — avoid the inertia and delay that may result. 7. Make sure your planned response is balanced, across: Communications, employee needs, travel, remote work, supply-chain, business tracking, and corporate responsibility. 8. Use resilience principles. Resilience requires ‘redundancy’ (2nd, 3rd sourcing of supplies), diversity (multiple approaches), modularity (assemble your business system in different ways), Evolvability (adapt and change, fast!), prudence (avoid hysteria), and embeddedness (live your values, don’t survive at others’ expense). 9. Prepare now for the next crisis (expect more troubles after COVID-19). 10. Intellectual preparation is not enough. (Set up a small war room, practice various scenarios). 11. Reflect on what you’ve learned. 12. Prepare for a changed world. We won’t be the same world after all this blows over.

It sounds trite, but – crises are opportunities. At the end of February 2003, when the SARS crisis broke out and Chinese businesses went into lockdown, Alibaba, under Jack Ma, organized the construction of its new on-line platform, with people working from home and communicating by phone and modem.

Alibaba’s market capitalization today is $547 billion.

Why COVID-19 Will Hurt the Global Economy

By Shlomo Maital

COVID-19 Map

The ‘new coronavirus’ dubbed boringly COVID-19 has brought to mind an insight of Charles Darwin:

It is not the species best adapted to their environments, that thrive and prosper, but rather, those who learn fastest to adapt to changes in their environment.

The reason? Environments are constantly changing. Living species have to adapt, and some do it far better than others.

Viruses are an example. Keep in mind- viruses are not actually living things, as cells are. A virus is a small infectious agent that reproduces only inside the living cells of an organism. It inserts its ribonucleic acid (RNA) into the DNA of the cell, reproduces, kills the cell, bursts out and continues with its marauding raid on the human body, like Genghis Khan’s pony-mounted fighters.

Viruses can infect all types of life forms. And they have learned, through evolution and mutation, to defeat the human body’s antibodies – soldier cells that attack and kill foreign invaders, or antigens. Viruses learn and adapt fast.

And we humans?

The damage to the global economy from the COVID-19 virus will be greater than we expect. World capital markets, down 10% and more, are now waking up to this fact. But why?

Most economic downturns occur on the demand side of the supply-demand nexus. Some shock occurs, people cut back, spend less, invest less, governments slash spending, exports fall – and the fall in demand slows the economy. This is standard, and it describes every single economic downturn.

When President Reagan implemented huge tax cuts in 1981 and then again in 1984, he ascribed them to ‘suppy side economics’ – desire to boost the supply of saving and capital, by putting more income in the hands of the wealthy. It worked – but not in the way Reagan thought. The rich spent the money, there was a huge demand boom, and America had a decade-long demand-side stimulus boom.

COVID-19 is unique, because it is the first major supply-side disaster, since the global economy’s architecture was redesigned and rebuilt at Bretton Woods, NH, in July 1944, 76 years ago. China produces a great many of the world’s manufactured goods and parts. Most of its factories have slowed or closed. This is a huge disruption to the intricate system of global supply chains.

What can be done? Very little, because we have neglected supply side policies, and have underestimated how fragile and delicate the global supply chain system is.

Central banks can slash interest rates, but interest rates are already rock bottom. Governments can spend money, but they already are running big deficits.

And anyway, these are demand-side policies. Yes, they can help soften the demand problems arising from the supply shocks – tourism is collapsing, airlines are in trouble, etc. But these are secondary symptoms.

How to restore the global supply chain? That’s the key issue. It requires a meeting of the world’s leading countries; meanwhile global companies like Apple are scrambling to find quick temporary fixes, and there are few good ones.

Darwin was right. Our environment changed, when a tiny virus originating in Wuhan, China, set out to spread itself. How fast we learn to adapt will determine how costly that little virus will be to the world.

Six Facts About the Wuhan Coronavirus

By Shlomo Maital

Wuhan coronavirus

Here are six things you should know about the Wuhan coronavirus, now sowing panic worldwide. (Based in part on Dr. Dan Werb’s New York Times article.) [1]

- China is an integral part of the global economy, and its factories supply parts for other countries’ supply chain ecosystems. China’s economy itself is 20% of the world economy – so any negative impact on China’s economy impacts the world directly, at once, and indirectly, over time. I know Israeli hi-tech firms whose products are made in China that have already been hard hit. The Wuhan virus is teaching the world that ‘globalization’ is a fact and that when the virus bell tolls, it tolls for everyone everywhere.

- A key data point is so-called R0 – how many additional people are infected, on average, when one person falls ill with the coronavirus? The answer is, apparently, 1.4 to 2.5. Is this good or bad? Both. It is higher than SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome), whose R0 is only 0.5. It is far lower than measles or polio. And it is just a bit higher than seasonal flu. But the point is, it does spread easily and rapidly.

- Another key data point: How deadly is it? Not very. About 2% of those who fall ill die from it, mainly from pneumonia and after-effects. Those who die are mostly those whose immune system and general health are poor. And in any event, a lot more people die of seasonal flu than from coronavirus. But don’t forget, that 2% does not really matter. If you can die from it, then the coronavirus sows panic — we humans are poor at perceiving accurately probabilities, and if something bad CAN happen, then we (rightly) worry that it WILL.

- Why did it start in China? Ducks and pigs. Chinese farms raise both. Ducks eat parasites in rice paddies, so they do good. But their “unique biology” makes them repositories for “a vast number of viruses”, while with pigs, various strains of viruses mix together and evolve and mutate into new strains able to infect humans (e.g. swine flu). Having said that, it appears that the Wuhan coronavirus may have come from bats or other animals, sold in a Wuhan market.

- What is coronavirus? Why is it called that? According to Dr. Werb, “The family of coronaviruses (so-called because they resemble glowing crowns) that includes the new Wuhan strain are exceptionally challenging to control. It gets its name from the shape of the virus, like a kind of crown, (corona is ‘crown’ in Latin) or like the circular corona of the sun. Coronaviruses are responsible for the common cold, pneumonia and bronchitis, but the coronavirus family is sprawling and includes deadlier outliers like Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), which have fatality rates of up to 15 percent and 35 percent, respectively.”

- Why can’t we just take a pill or a vaccine shot and solve the problem? Why doesn’t the body’s own system of antibodies defeat them? Viruses in general, and coronaviruses in particular, are really ‘smart’. Here is what I learned about how they foil the immune system.

“When a virus enters the body, a race begins between responding immune cells and the infecting pathogen. The pathogen replicates and finds a target cell or organ that will allow it to thrive. So, the effectiveness of a response depends on the immune system winning the race to clear the pathogen before it causes irreversible damage to the body. Immune cells called “B cells” make antibodies. A pathogen such as a virus is a large molecule with different components, called antigens. When a B cell recognizes an antigen, it is activated and interacts with other immune cells to receive directions. When an “invader” cell attacks, the body’s immune system checks its ‘memory’ to see if it has seen it before. Because memory cells have already undergone quality improvement, they can respond quickly after reinfection to produce a large number of plasma cells secreting high-quality antibody. Therefore, memory cells can clear the infection much more rapidly than the initial infection. This means the pathogen doesn’t have time to damage the body. However viruses change, mutate and evolve. Flu is highly variable and changes each season, or evolves in ducks and pigs; variations are why we require yearly vaccinations. And with Wuhan coronavirus, which ‘surprised’ the world, no vaccine exists yet, nor will we have one for many months.”

[Source: http://theconversation.com/explainer-how-viruses-can-fool-the-immune-system-43707%5D

So, what is my prediction? Will coronavirus become a global pandemic, like the 1918-19 infuenza epidemic that killed between 20 million and 40 million people, more than in World War I (including my grandfather Israel)? Or will we manage to control it?

No, it will not become a pandemic. It will slash a few points of global growth. We should learn the main lesson that Wuhan coronavirus comes to teach us. We have created a superb global ecosystem, where nations become wealthy by doing what they do best and selling the result to others, buying from others what THEY do best. This creates an enormous interdependent ecosystem, with major advantages but one big disadvantage – any bad virus that starts in one place spreads rapidly all over, because of millions who travel regularly. Shutting down travel, and trade, is devastating, but at times necessary. And there will be lots of those viruses, because they are very clever, they change, mutate and adapt, and continually surprise us, making off-the-shelf solutions irrelevant and fooling our immune systems regularly.

We will need a new, efficient, clever and rapid global cooperative mechanism to deal with this new threat. But the current political poison against global cooperation may make this really difficult to attain.

[1] Dr. Dan Werb, New York Times, Jan. 30/2020, To Understand the Wuhan Coronavirus, Look to the Epidemic Triangle.