You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘education’ tag.

Looking is Better Than Knowing

By Shlomo Maital

Goethe once said “Thinking is better than knowing — but looking is best of all”.

I am an economist. Economists do a lot of thinking. Based on their thinking, often couched in terms of mathematics, they do a lot of knowing. But looking?

Ever since the economics profession opted for Leon Walras’ complex mathematics, over Alfred Marshall’s reality-based economics, around 1880, economics has chosen mathematical elegance in place of reality. “Elegance is for tailors”, MIT Economist Paul Samuelson once said, but he too leaned heavily on mathematics.

The peak of this economic fantasy was J.K. Galbraith’s 1967 book The New Industrial State. In it, Galbraith described the new economics powered by huge industrial giants. But he baldly stated, I have never been inside a factory. Never. Yet his book was a best-seller and was swallowed whole, by all.

Economics today is different. It has at last embraced ‘looking’ in place of ‘thinking’, through behavioral economics, led by the massive influence of, get this, two psychologists, the late Amos Tversky and the late Daniel Kahneman. Behavioral economics studies people and how they behave, in place of scribbling equations and pretending they describe reality.

Until 2001, I was part of the ‘thinking’ fantasy brigade. I took early retirement and went out to teach and study creativity, innovation and hi-tech. I worked with large companies and small startups – and only then, began to understand the reality of innovation-driven economics. I wrote a book, only after enlisting a former student who had made a brilliant career in advertising, built on innovation, as co-author.

Here is how I would reinvent the way economists are trained. I would adopt the MD/PhD model. In this program, which exists at Harvard, Penn and Stanford, students do a full medical degree, including an internship working on hospital wards, and at the time time, do a PhD, in which they learn to do research. Together, the life experience of treating sick patients and the rigorous training to do research, leads to reality-based research that changes the world.

This is how I would train economics students today. A rigorous training in research – and a lengthy internship in factories, and other places of work, to observe, befriend and work with real people.

Prof. Aaron Ciechanover, at my university Technion, won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for identifying the protein, ubiquitin, that causes cells to die when they re no longer viable. He holds an MD/PhD degree, and credits his clinical MD training for helping to make his research more anchoered, realistic and powerful.

Drew Weissman won the Nobel Prize in 2023, along with Penn colleague Katalin Koriko, for showing how mRNA could create effective vaccines – leading to the Pfizer/Moderna vaccine that saved 20 million lives. Weissman is an MD and a PhD as well. It is no coincidence.

It sounds very simple. But looking should be a strong part of all academic training. Not just thinking. The scholars and creative people who change the world are almost all expert at looking. Economics spent 150 years just thinking. I think it led to disastrous policies. We should be begging the world for forgiveness.

America! Open the Windows!

By Shlomo Maital

One of the most annoying things about MAGA Make America Great Again is this:

The basic premise of MAGA is, America is NOT great, at present. Understatement. Poor healthcare. Unaffordable housing. Poor schools. Wealth and income inequality. Racism. Antisemitism. Polarized paralyzed politics… just for a start.

So, how to make America great again? Place a Nazi sympathizer in charge of destroying public services. Smash alliances abroad, suck up to dictators, appoint incompetent loyalists to key positions, engage in vengeance, ….

There is another way. It is found in this new book, Another World Is Possible: Lessons for America from Around the Globe. – by Natasha Hakimi Zapata. 2025

The simple, obvious, key point – overlooked by the current Administration. Other countries, far less wealthy, have solutions to America’s problems. Right under our noses. But American exceptionalism means, that is not possible. Because .. well, just because.

Singapore (NOT a leftist socialist liberal country) has extraordinary affordable public housing. I’ve seen it first hand. Check it out, America.

Canada has national health insurance. I was born in Saskatchewan, the first province to implement it, in the 1950’s. Check it out, America. Canadians all have health insurance. So do the British – and most civilized European countries.

Estonia has income tax filing online. Fast, simple, easy. Check it out, America.

Most German public universities (and they are mostly outstanding) charge no tuition. America? Michigan has great state universities – but if you don’t live in the state, you pay $60,000 – $65,000 tuition yearly. Not including room and board.

Schools? America is not among the top scoring countries according to the PISA benchmark. Not even close. Way behind China.

Housing, healthcare, education, public services, ….things that drive our quality of life. America trails, despite high GDP per capita.

Why? Closed windows. Other countries have found wise, pragmatic solutions to key problems. The US refuses to learn from them. Costa Rica? Denmark? Learn from them? Get serious, American politicians spout.

In years of teaching managers, I taught them how to define their key operations (marketing, quality assurance, production, innovation) and benchmark which other companies did these things best, how they did them, and – learn from them, adapt and adopt. Pretty simple idea. Best practice benchmarking. Works for nations too. Yes, even for America.

Learn from others.

The most blatant stupidity is Trump’s desire to annex Canada. Why in the world would any Canadian choose to be part of a nation that is hopelessly divided politically and systematically destroying its public services? A country that blindly asserts its superiority, against all evidence, while refusing to learn from others wiser and smarter?

Natasha Hakimi Zapata’s book is MUST reading for MUSK. But don’t hold your breath.

How Everyone Can Be Better Than Average:

Why “No Child Left Behind” Leaves Kids Behind

By Shlomo Maital

In Garrison Keillor’s wonderful radio program Prairie Home Companion, that aired live from 1974 to 2016 – an incredible 42 years! — Keillor did regular segments on “Lake Wobegone” where “all the children are above average”.

He always ended the segment with these words: “Well, that’s the news from Lake Wobegon, where all the women are strong, all the men are good-looking, and all the children are above average.”

Now, all the children cannot be above average, if you understand what an average is.

But in fact – it turns out, in one sense, they CAN!! Let me explain.

In his excellent New York Times Op-Ed (Tuesday June 18, international edition), Alfie Kohn asks, Why Can’t Everyone Get A’s? he makes the distressing point that America’s educational system has for two decades been built on the wrong belief that “excellence is a zero-sum game”.

Why?

When George W. Bush was elected President in 2000 (actually, he lost, but Florida’s Republican Supreme Court screwed Democrat candidate Al Gore), the first thing he did was initiate No Child Left Behind legislation. That law mandated widespread standardized testing in US schools. The idea, based on free-market economics, was – you promote excellence only by measuring it.

But – how do you measure it?

My wife Sharone, an experienced school psychologist, explained the two alternate ways of assessment: a) norm-reference tests, and b) criterion-reference tests. Please take a moment to understand the difference:

Norm-referenced tests report whether test takers performed better or worse than a hypothetical average student, which is determined by comparing scores against the performance results of a statistically selected group of test takers, typically of the same age or grade level, who have already taken the exam.

A criterion-referenced test is a style of test which uses test scores to generate a statement about the behavior that can be expected of a person with that score. Most tests and quizzes that are written by school teachers can be considered criterion-referenced tests.

Let’s simplify. Norm reference tests are tests ‘on a curve’. There are always those who excel, and always those who flunk. It’s the nature of a curve. Zero sum.

No Child Left Behind was based on norm reference tests. And as a result a great many kids were and are being left behind.

There is a better way. Define a criterion for excellence, or anything else you want to measure. For instance: Answering 80% or more math questions correctly.

Test kids. See how many meet the criterion. The goal: Let every kid be ‘above average’, like in Lake Wobegone, where ‘average’ means ‘meeting the criterion’.

With norm reference tests, 20% of kids, for instance, will get A’s. No matter how hard the rest study, or learn, only 20% can get an A. It’s zero sum.

With criterion reference tests, EVERYONE can potentially get an A.

When schools report a high number of A’s, experts say, “grade inflation”. Why? Isn’t the goal of education to be inclusive, to help EVERYONE get an A, to make sure that truly, no child is left behind?

But norm reference tests BY DEFINITION leave 80%, say, behind.

Everyone CAN get A’s. Everyone can be above ‘average’, as in Lake Wobegone. America has sold a dangerous, false educational ideology to the world, including my country Israel.

It’s time to rethink how we assess our kids.

Why We Do What We Do – Putting it All Together

By Shlomo Maital

Sometimes things just seem to come together, naturally.

- I recently taught a Workshop for a wonderful group of high school science teachers. They all told me, their key problem is – motivating their students. Motvating them to learn.

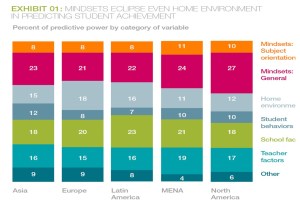

- I recently received a research paper from McKinsey, titled “How to improve student educational outcomes: New insights from data analytics”. In this study McKinsey researchers used machine learning (an offshoot of artificial intelligence) to analyze a massive data set — the PISA surveys of 15 year old high school students and their understanding of science and math. The key finding: Student mindsets are twice as predictive of students’ PISA scores than even their home environments. Mindset means “a student’s sense of belonging, motivation and expectations”. This result is robust across the entire world.

The graph shows the % of predictive power of students’ performance. The top two rectangles (orange and purple) represent “mindset” (motivation), for the five different geographical areas.

- My wife’s copy of the American Psychological Association magazine Monitor just arrived. In it, 33 leading psychologists were asked, “What is the next big question psychology needs to answer?” The first person quoted was Stanford Psychologist Carol Dweck, whose work on growth mindsets (the idea that talent and talent can grow in a nurturing education environment) was seminal. She said we need “an integrative theory of motivation” and “a framework for …effective intervention [to boost motivation].

These three circles converge. They teach us that how well we motivate ourselves, and those we work with, are THE crucial variables. Because motivated people can do anything (did you watch the Croatia soccer team at the World Cup?). And those without motivation can do nothing.

Let’s look inward and ask, what lights our spark? And then look outward and ask, how can we light the sparks of others who work with us?

Lifelong Kindergarten: Reinventing How We Educate Our Kids

By Shlomo Maital

When my wife and I were raising our four children, I recall bringing them to kindergarten some mornings. Secretly, and often, I wished I could stay there with them and play. Can I join? Can I play too? With blocks, crayons, Lego? I even thought of trying to set up adult kindergartens, where grown-ups could become kids again and relearn how to play. That happens again, when I pick up our grandchildren from pre-school.

This is why I loved Mitchel Resnick’s new book, Lifelong Kindergarten; Cultivating Creativity Through Passion, Peers, Projects and Play (MIT Press, 2016). Resnick, an MIT Media Lab professor, says correctly that “most schools in most countries place a higher priority on teaching students to follow instructions and rules, than on helping students develop their own ideas, goals and strategies.”

The reason? Public education, one of the world’s greatest inventions, was designed to produce workers for the first industrial revolution – for factories. But we are now in the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Robots and artificial intelligence will do the routine work. We need creative people. But we haven’t yet figured that out, and so our schools remain mired in the 19th C.

The best kindergartens are places where children learn through playing together. The operative word is “learn”. There is enough structure to guide their learning. But not so much as to destroy their initiative and creativity.

Worldwide, kindergartens are becoming more like schools. Small children are getting homework and work sheets. The opposite should happen. Schools should become more like kindergartens. Resnick proposes four P’s – passion, play, peers and projects. Ignite kids’ passion. Let them learn through discovery, by working on projects together. This, of course, is how they will work as adults. And while the learning is serious, let it seem like play.

As a retired but still active professor at an engineering school, Technion, I feel we are centuries behind in understanding how to reinvent education. Somehow, our students survive the rigid structured program and retain at least some of their creativity. Many launch startups.

But – how much “creativity capital” (the present value of ideas lost because our backward educational system, focused on rules and solving canned problems, extinguishes creative ideas) is destroyed – and ignored, because it is largely hidden and unmeasured?

Can we as parents and grandparents do anything? Here is one small step. When you buy toys for children – ask not (Resnick says) what the toy can do for the child. Ask, what can the child do with the toy? Buy toys that stimulate creativity by letting the child decide what to make, what to invent, what to dream. Understand that there is a reason why kids take a toy out of the box – and then play imagination games with the box.

High School Tech: What Schools COULD Become

By Shlomo Maital

In another wonderful column, David Brooks (NYT Oct. 16) describes a documentary film, Most Likely to Succeed, by Greg Whiteley, in which San Diego’s High Tech High is featured, started by San Diego high tech and business leaders. I can do no better than to quote Brooks’ words:

Greg Whiteley’s documentary argues that the American school system is ultimately built on a Prussian model designed over 100 years ago. Its main activity is downloading content into students’ minds, with success or failure measured by standardized tests. This lecture and textbook method leaves many children bored and listless.

Worse, it is unsuited for the modern workplace. Information is now ubiquitous. You can look up any fact on your phone. A computer can destroy Ken Jennings, the world’s best “Jeopardy!” contestant, at a game of information retrieval. Computers can write routine news stories and do routine legal work. Our test-driven schools are training kids for exactly the rote tasks that can be done much more effectively by computers.

In High Tech High….There are no textbooks, no bells… Students are given group projects built around a driving question. One group studied why civilizations rise and fall and then built a giant wooden model, with moving gears and gizmos, to illustrate the students’ theory. Another group studied diseases transmitted through blood, and made a film. “Most Likely to Succeed” doesn’t let us see what students think causes civilizational decline, but it devotes a lot of time to how skilled they are at working in teams, demonstrating grit and developing self-confidence. There are some great emotional moments. A shy girl blossoms as a theater director. A smart but struggling boy eventually solves the problem that has stumped him all year. In the school, too, teachers cover about half as much content as in a regular school. Long stretches of history and other subject curriculums are effectively skipped. Students do not develop conventional study habits.

Brooks is not uncritical of High Tech High. In this blog, I have also made the point that in order to foster creativity, you cannot discard the hard tough discipline of mastery – mastering old knowledge, while thinking about how to create new. Brooks echoes this thought.

The cathedrals of knowledge and wisdom are based on the foundations of factual acquisition and cultural literacy. You can’t overleap that, which is what High Tech High is in danger of doing. “Most Likely to Succeed” is inspiring because it reminds us that the new technology demands new schools. But somehow relational skills have to be taught alongside factual literacy. The stairway from information to knowledge to wisdom has not changed. The rules have to be learned before they can be played with and broken.

This is worth repeating. Innovation is INTELLIGENTLY breaking the rules. In order to break the rules intelligently, creatively, first you have to learn them. You have to know physics, to engineer wonderful new devices. The key is, can we teach physics, without ruining the creative spark in those we teach?

Touchstone School: “Magical Moments”

By Shlomo Maital

My wife and I are visiting Touchstone Community School, here in Grafton, MA, about an hour from Boston. In this and several following blogs, I would like to recount briefly some ‘magical moments’ I experienced there, in a pre-K to Grade 8 school where children do not take formal tests and where their imaginations and social skills are fostered.

Background: Thanks to the hospitality of Touchstone, I’ve brought a Chinese family from Shantou, Guangdong (where Technion has a joint venture program), to visit the school – Jin, my former Shantou U. student, his wife Yuen, and 3-year-old daughter Yue, or Sophia. Together we’re making a documentary film, hoping to bring the message of Touchstone’s “transformative schooling” back to China and to Israel.

Sophia and her new friend…language is no barrier!

Sophia and her new friend…language is no barrier!

Values: We joined a group of Grade 7-8 children discussing Touchstone core values. The class itself had earlier chosen core values: all began with “C” — Confidence, curiosity, connection, creativity. These values appeared on a ‘flag’ created by the children which included one square per child, where the square reflected the child’s own personality. This emphasis at Touchstone on being an individual is pervasive.

I asked the students about rules. If you have core values, and act on them, do you really need rules? Rules are external, externally enforced; values are internal, internally enforced. The discussion was interesting, the consensus was – values can replace rules.

There followed a discussion about table arrangements. Pairs? Fours? One big square table? The consensus was: One big table, more inclusive. Inclusiveness is a school-wide core value. I suggested, maybe a oval or round table? But there is no such table at Touchstone. However, there is an oval carpet. Let’s sit around the carpet, the students suggested. I came up with a round table that splits into four segments, so work in pairs and small teams can take place. We need to have it built.

One conversation at a time? This is an IDEO principle. It is implemented in this class with Jupiter, a soft toy, tossed from one child (the speaker) to another (who raises their hands and wishes to speak). One child was applauded, for actually catching Jupiter with one hand (apparently, a first! The students joked about it…not in a mocking manner).

I could not help but notice the huge developmental gap between the girls and the boys…the girls are way way ahead of the boys, which is common at this age.

There is a core issue here. Teachers who graduate from teachers’ colleges learn about the rules of pedagogy and the rules of schooling. They then implement those rules in the schools where they teach, and children learn about following an external set of rules, with punishments (and rewards, at times). Children who follow rules well, do well in school. Rebellious kids don’t. But creativity demands rebellion. Are we eradicating it with our rule-based system? Touchstone begins with values. Values are internal. Why not replace external rules with internal values? And make ‘confidence’, and ‘creativity’ core values?

New Thinking About Our Schools: It’s NOT Rocket Science!

By Shlomo Maital

A great many people the world over are troubled about what happens to our children and grandchildren in the school system. America’s No Child Left Behind Act (2000) has left most children behind, because America still scores poorly in international achievement tests, despite (because of?) billions spent on “Race to the Top”.

A simple principle says, if you want to improve, learn from others. Benchmark what others do, adapt it, and get better. But educational bureaucracies in most countries do not even know what global benchmarking is.

Take Finland, for example. Pasi Sahlberg, a Finnish educator, has shared Finland’s experience with the world in his 2011 book Finnish Lessons: What Can the World Learn from Educational Change in Finland? It has been translated into many languages already, including Hebrew.

Here are the four key principles Finland used to create a world-class world-leading educational system, for all Finnish kids, not just a handful of privileged ones in Helsinki.

- Guarantee equal opportunities to good public education for all. In the U.S., that means that schools in rural Louisiana and Mississippi should be up to scratch, as much as ones in Princeton, NJ.

- Strengthen professionalism of, and trust in, teachers. This is related to pay levels, teachers’ colleges, and in general, how society values those who educate our children. In Finland, it’s really hard to get in to teaching programs, as hard as getting in to engineering.

- Get parents involved, educate everyone about education and the key processes, especially assessment (and note: assessment is NOT just tests).

- Facilitate competition and innovation among schools; network them, help them learn quickly from one another, let them try experiments and scale up ones that succeed.

These principles are easy to state, hard to implement. But take #4, for example. President Bush’s very first Act, in 2000, brought free-market competition models to American schools by tying state and federal funding for schools to test performance of kids. Many countries have copied this dumb idea.

There is another way to introduce competitive forces into education. Let schools experiment, and share the results. This is the REAL free-market model. To do this, you need to abandon the insane obsession with testing, hated by kids, parents and teachers alike, and let kids learn to love learning, let teachers love to teach, and evaluate by what children can do, rather than what they can memorize and regurgitate.

In Finland, it worked. How come? What can we learn from it? How many American educators have spent time in Finland, observing their schools, talking to their educators? And how long will it take, before educational professionals all realize that No Child Left Behind left a great many kids behind, far behind, and that it is time to dump the whole bad idea, not only in America but everywhere.

How Teachers Ruin Inquiring Minds – And Why They Must Stop

By Shlomo Maital

Illustration by Avi Katz

Thanks to my outstanding colleagues at Technion’s Center for Improvement of Teaching and Learning, our MOOC (massive open online course), Cracking the Creativity Code: Part One – Discovering Ideas, launched on the Coursera website on May 18, and has over 6,000 students enrolled, worldwide, from Qatar, India, China, Iran, Iraq and Saudi Arabia, among others. The course is based in part on the book by the same name by Ruttenberg & Maital.

Part of the course involves “chat” forums, organized as ‘forums’ on topics the students themselves initiate.

Lizzie writes: “My 7th grade teacher’s response to many a question was ‘don’t show your ignorance by asking that’. Which didn’t reduce my ignorance but did get me to stop asking questions and start hating school instead of loving it.” Malgorzata responds: “Oh yes. I have suffered high school phobia because of it. Constant bullying by teachers was unbearable.”

How many teachers encourage questions? How many shut them off, destroying the spirit of inquiry and love of learning? Are teacher training schools helping teachers encourage students’ questions, rather than shutting them off?

Javier writes about how his teacher, in Barcelona, requires the students to copy verbatim a short story. He tried an experiment – writing with his eyes closed, to see if he could write straight lines without looking. The teacher ridiculed him before the class. End of experiment. Could the teacher have responded: Class! Javier is trying to write with his eyes closed. Let’s all try it. Let’s see what happens. Javier, thank you for this interesting idea.!

There are millions of superb, dedicated teachers all over the world, educating the next generation, overworked, underpaid, underappreciated. But there are still too many to believe they should be teaching the laws of algebra, rather than (in addition) why mathematics is interesting and fun to explore.

The Nobel Laureate in Physics Isidore Rabi tells this story: When he came home from school, his mother never asked him, what did you learn today in school? Instead she asked, Isador, did you ask good questions in class today? He attributes his success as a scientist to his mother and to her question. How many Nobel Prizes are we destroying, by shutting off kids’ questions?