You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘COVID-19’ tag.

Roubini’s Black Swan, Coronavirus Variety

By Shlomo Maital

Nuriel Roubini

Nuriel Roubini is famous for his book on Black Swans – totally unexpected events, whose possibility is denied (as people denied there were such things as black swans) and which occur with massive impact on our lives. COVID-19 is definitely the blackest of black swans….

Roubini is massively pessimistic. While I myself am far more optimistic – I see the ‘apex’ of the plague coming fairly soon, and then as the curve declines, optimism, stock prices and businesses recover and bounce back and spend to ‘catch up’ — I feel I should bring you readers the other side of the moon, the dark side, the black (swan) side. So, here is Roubini’s ‘take’. Everybody should figure out their own personal scenario… [Warning, this blog is twice as long as usual]

NEW YORK – The shock to the global economy from COVID-19 has been both faster and more severe than the 2008 global financial crisis (GFC) and even the Great Depression. In those two previous episodes, stock markets collapsed by 50% or more, credit markets froze up, massive bankruptcies followed, unemployment rates soared above 10%, and GDP contracted at an annualized rate of 10% or more. But all of this took around three years to play out. In the current crisis, similarly dire macroeconomic and financial outcomes have materialized in three weeks.

Earlier this month, it took just 15 days for the US stock market to plummet into bear territory (a 20% decline from its peak) – the fastest such decline ever. Now, markets are down 35%, credit markets have seized up, and credit spreads (like those for junk bonds) have spiked to 2008 levels. Even mainstream financial firms such as Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan and Morgan Stanley expect US GDP to fall by an annualized rate of 6% in the first quarter, and by 24% to 30% in the second. US Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin has warned that the unemployment rate could skyrocket to above 20% (twice the peak level during the GFC).

In other words, every component of aggregate demand – consumption, capital spending, exports – is in unprecedented free fall. While most self-serving commentatorshave been anticipating a V-shaped downturn – with output falling sharply for one quarter and then rapidly recovering the next – it should now be clear that the COVID-19 crisis is something else entirely. The contraction that is now underway looks to be neither V- nor U- nor L-shaped (a sharp downturn followed by stagnation). Rather, it looks like an I: a vertical line representing financial markets and the real economy plummeting.

Not even during the Great Depression and World War II did the bulk of economic activity literally shut down, as it has in China, the United States, and Europe today. The best-case scenario would be a downturn that is more severe than the GFC (in terms of reduced cumulative global output) but shorter-lived, allowing for a return to positive growth by the fourth quarter of this year. In that case, markets would start to recover when the light at the end of the tunnel appears.

But the best-case scenario assumes several conditions. First, the US, Europe, and other heavily affected economies would need to roll out widespread COVID-19 testing, tracing, and treatment measures, enforced quarantines, and a full-scale lockdown of the type that China has implemented. And, because it could take 18 months for a vaccine to be developed and produced at scale, antivirals and other therapeutics will need to be deployed on a massive scale.

Second, monetary policymakers – who have already done in less than a month what took them three years to do after the GFC – must continue to throw the kitchen sink of unconventional measures at the crisis. That means zero or negative interest rates; enhanced forward guidance; quantitative easing; and credit easing (the purchase of private assets) to backstop banks, non-banks, money market funds, and even large corporations (commercial paper and corporate bond facilities). The US Federal Reserve has expanded its cross-border swap lines to address the massive dollar liquidity shortage in global markets, but we now need more facilities to encourage banks to lend to illiquid but still-solvent small and medium-size enterprises.

Third, governments need to deploy massive fiscal stimulus, including through “helicopter drops” of direct cash disbursements to households. Given the size of the economic shock, fiscal deficits in advanced economies will need to increase from 2-3% of GDP to around 10% or more. Only central governments have balance sheets large and strong enough to prevent the private sector’s collapse.

But these deficit-financed interventions must be fully monetized. If they are financed through standard government debt, interest rates would rise sharply, and the recovery would be smothered in its cradle. Given the circumstances, interventions long proposed by leftists of the Modern Monetary Theory school, including helicopter drops, have become mainstream.2

Unfortunately for the best-case scenario, the public-health response in advanced economies has fallen far short of what is needed to contain the pandemic, and the fiscal-policy package currently being debated is neither large nor rapid enough to create the conditions for a timely recovery. As such, the risk of a new Great Depression, worse than the original – a Greater Depression – is rising by the day.

Unless the pandemic is stopped, economies and markets around the world will continue their free fall. But even if the pandemic is more or less contained, overall growth still might not return by the end of 2020. After all, by then, another virus season is very likely to start with new mutations; therapeutic interventions that many are counting on may turn out to be less effective than hoped. So, economies will contract again and markets will crash again.

Moreover, the fiscal response could hit a wall if the monetization of massive deficits starts to produce high inflation, especially if a series of virus-related negative supply shocks reduces potential growth. And many countries simply cannot undertake such borrowing in their own currency. Who will bail out governments, corporations, banks, and households in emerging markets?

In any case, even if the pandemic and the economic fallout were brought under control, the global economy could still be subject to a number of “white swan” tail risks. With the US presidential election approaching, the COVID-19 crisis will give way to renewed conflicts between the West and at least four revisionist powers: China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea, all of which are already using asymmetric cyberwarfare to undermine the US from within. The inevitable cyber attacks on the US election process may lead to a contested final result, with charges of “rigging” and the possibility of outright violence and civil disorder.1

Similarly, as I have argued previously, markets are vastly underestimating the risk of a war between the US and Iran this year; the deterioration of Sino-American relations is accelerating as each side blames the other for the scale of the COVID-19 pandemic. The current crisis is likely to accelerate the ongoing balkanization and unraveling of the global economy in the months and years ahead.2

This trifecta of risks – uncontained pandemics, insufficient economic-policy arsenals, and geopolitical white swans – will be enough to tip the global economy into persistent depression and a runaway financial-market meltdown. After the 2008 crash, a forceful (though delayed) response pulled the global economy back from the abyss. We may not be so lucky this time.

Small Acts of Kindness…Are Really Big!

By Shlomo Maital

This morning, I rose early and went to shop for food at our local small grocery store. As first in line, I got to shop quickly — Y., the shopkeeper, was strict in limiting contact between shoppers and only let one or two of us in, at a time.

When I exited, loaded the groceries in the car and returned the shopping cart, a truck driver spotted me; he was delivering sanitary supplies. He cautioned me gently to use gel on my hands because the cart handle could have been infected. I think he noticed my grey hair and was concerned. I did as he said, and then – he gave me a pair of rubber gloves from his truck, and some highly prized alco-gel. I wished him well, he did the same…

This small incident touched me deeply. This truck driver is in the front line – he sees many people daily, some may be infected…. And yet, he is concerned for my wellbeing, and he doesn’t even know me. Same for Y. the shopkeeper. He too is in the front line. He makes sure we are all well stocked with groceries, including fresh fruits and vegetables, which Israel has aplenty.

These tiny acts of kindness, perhaps not so tiny, are happening all over the world. They embody a Hebrew saying, “All Israel is bonded one to another”… and I interpret that to mean, all humanity. We are NOT socially isolated, we are spatially separated and socially bonded. Tiny acts of kindness prove it.

Thanks, truck driver. And yes, I will indeed pass it forward – and so will we all.

Know the Enemy! Understanding the Coronavirus

By Shlomo Maital

Let’s try to understand this coronavirus enemy better, with the help of experts. (from the Washington Post, by Sarah Kaplan, William Wan and Joel Achenbach). Sorry, this blog is long, 1,500 words.

How long have viruses evolved? Are they actually ‘alive’?

“Viruses have spent billions of years perfecting the art of surviving without living — a frighteningly effective strategy that makes them a potent threat in today’s world. That’s especially true of the deadly new coronavirus that has brought global society to a screeching halt. It’s little more than a packet of genetic material surrounded by a spiky protein shell one-thousandth the width of an eyelash, and it leads such a zombielike existence that it’s barely considered a living organism. But as soon as it gets into a human airway, the virus hijacks our cells to create millions more versions of itself.

OK, so coronavirus is not alive …but how come it is so darn SMART?!

“There is a certain evil genius to how this coronavirus pathogen works: It finds easy purchase in humans without them knowing. Before its first host even develops symptoms, it is already spreading its replicas everywhere, moving onto its next victim. It is powerfully deadly in some but mild enough in others to escape containment. And for now, we have no way of stopping it. As researchers race to develop drugs and vaccines for the disease that has already sickened 350,000 and killed more than 15,000 people, and counting, this is a scientific portrait of what they are up against.

How to respiratory viruses like coronavirus make us ill?

“Respiratory viruses tend to infect and replicate in two places: In the nose and throat, where they are highly contagious, or lower in the lungs, where they spread less easily but are much more deadly. This new coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, adeptly cuts the difference. It dwells in the upper respiratory tract, where it is easily sneezed or coughed onto its next victim. But in some patients, it can lodge itself deep within the lungs, where the disease can kill. That combination gives it the contagiousness of some colds, along with some of the lethality of its close molecular cousin SARS, which caused a 2002-2003 outbreak in Asia. Another insidious characteristic of this virus: By giving up that bit of lethality, its symptoms emerge less readily than those of SARS, which means people often pass it to others before they even know they have it. It is, in other words, just sneaky enough to wreak worldwide havoc.

So, we have to hand it to COVID-19 – it’s pretty darned smart. Even without a brain. All, through millions of years of evolution.

“Viruses much like this one have been responsible for many of the most destructive outbreaks of the past 100 years: the flus of 1918, 1957 and 1968; and SARS, MERS and Ebola. Like the coronavirus, all these diseases are zoonotic — they jumped from an animal population into humans. And all are caused by viruses that encode their genetic material in RNA. That’s no coincidence, scientists say. The zombielike existence of RNA viruses makes them easy to catch and hard to kill. Outside a host, viruses are dormant. They have none of the traditional trappings of life: metabolism, motion, the ability to reproduce. And they can last this way for quite a long time. Recent laboratory research showed that, although SARS-CoV-2 typically degrades in minutes or a few hours outside a host, some particles can remain viable — potentially infectious — on cardboard for up to 24 hours and on plastic and stainless steel for up to three days. In 2014, a virus frozen in permafrost for 30,000 years that scientists retrieved was able to infect an amoeba after being revived in the lab. When viruses encounter a host, they use proteins on their surfaces to unlock and invade its unsuspecting cells. Then they take control of those cells’ molecular machinery to produce and assemble the materials needed for more viruses.

How does coronavirus “proofread” errors, as it multiplies within the human body?

“Let’s say dengue has a tool belt with only one hammer,” said Vineet Menachery, a virologist at the University of Texas Medical Branch. This coronavirus has three different hammers, each for a different situation. Among those tools is a proofreading protein, which allows coronaviruses to fix some errors that happen during the replication process. They can still mutate faster than bacteria but are less likely to produce offspring so riddled with detrimental mutations that they can’t survive. Meanwhile, the ability to change helps the germ adapt to new environments, whether it’s a camel’s gut or the airway of a human unknowingly granting it entry with an inadvertent scratch of her nose.

Where did coronavirus come from?

“Scientists believe that the SARS virus originated as a bat virus that reached humans via civet cats sold in animal markets. This current virus, which can also be traced to bats, is thought to have had an intermediate host, possibly an endangered scaly anteater called a pangolin. “I think nature has been telling us over the course of 20 years that, ‘Hey, coronaviruses that start out in bats can cause pandemics in humans. Such viruses usually simply cause colds and were not considered as important as other viral pathogens, he said. think of them as being like influenza, as long-term threats,’” said Jeffery Taubenberger, virologist with the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Funding for research on coronaviruses increased after the SARS outbreak, but in recent years that funding has dried up.

Why is it proving so hard to come up with ‘weapons’ to fight coronavirus?

“Most antimicrobials work by interfering with the functions of the germs they target. For example, penicillin blocks a molecule used by bacteria to build their cell walls. The drug works against thousands of kinds of bacteria, but because human cells don’t use that protein, we can ingest it without being harmed. But viruses function through us. With no cellular machinery of their own, they become intertwined with ours. Their proteins are our proteins. Their weaknesses are our weaknesses. Most drugs that might hurt them would hurt us, too.

“For this reason, antiviral drugs must be extremely targeted and specific, said Stanford virologist Karla Kirkegaard. They tend to target proteins produced by the virus (using our cellular machinery) as part of its replication process. These proteins are unique to their viruses. This means the drugs that fight one disease generally don’t work across multiple ones. And because viruses evolve so quickly, the few treatments scientists do manage to develop don’t always work for long. This is why scientists must constantly develop new drugs to treat HIV, and why patients take a “cocktail” of antivirals that viruses must mutate multiple times to resist.

“Modern medicine is constantly needing to catch up to new emerging viruses,” Kirkegaard said. SARS-CoV-2 emerges from the surface of cells cultured in a lab. (National Institutes of Health/AFP). SARS-CoV-2 is particularly enigmatic. Though its behavior is different from that of its cousin SARS, there are no obvious differences in the viruses’ spiky protein “keys” that allow them to invade host cells. Understanding these proteins could be critical to developing a vaccine, said Alessandro Sette, head of the center for infectious disease at the La Jolla Institute for Immunology. Previous research has shown that the spike proteins on SARS are what trigger the immune system’s protective response. In a paper published this month, Sette found the same is true of SARS-CoV-2.

“This gives scientists reason for optimism, according to Sette. It affirms researchers’ hunch that the spike protein is a good target for vaccines. If people are inoculated with a version of that protein, it could teach their immune system to recognize the virus and allow them to respond to the invader more quickly.

“It also says the novel coronavirus is not that novel,” Sette said.

And if SARS-CoV-2 is not so different from its older cousin SARS, then the virus is probably not evolving very fast, giving scientists developing vaccines time to catch up.

“In the meantime, Kirkegaard said, the best weapons we have against the coronavirus are public health measures, such as testing and social distancing, and our own immune systems.”

Man oh man – this baby is a formidable enemy. And it’s not even alive. Maybe we all-powerful all-knowing human beings should be in future a little more modest about who we are and what we can do.

The World After COVID-19

By Shlomo Maital

What happens after the COVID-19 pandemic subsides? Two McKinsey (global consulting company) experts Kevin Sneader and Shubham Singhal provide some insights. This blog is rather long – warning!

They describe a five-stage process we need to manage: In order: the five R’s — Resolve, Resilience, Return, Reimagine, Reform.

First point: Everything, everything will change.

“It is increasingly clear our era will be defined by a fundamental schism: the period before COVID-19 and the new normal that will emerge in the post-viral era: the “next normal.” In this unprecedented new reality, we will witness a dramatic restructuring of the economic and social order in which business and society have traditionally operated. And in the near future, we will see the beginning of discussion and debate about what the next normal could entail and how sharply its contours will diverge from those that previously shaped our lives. Collectively, these five stages represent the imperative of our time: the battle against COVID-19 is one that leaders today must win if we are to find an economically and socially viable path to the next normal.”

The authors then note a five-stage process for moving forward:

Step One. Resolve “ …a toxic combination of inaction and paralysis remains, stymying choices that must be made: lockdown or not; isolation or quarantine; shut down the factory now or wait for an order from above. That is why we have called this first stage Resolve: the need to determine the scale, pace, and depth of action required at the state and business levels. As one CEO told us: “I know what to do. I just need to decide whether those who need to act share my resolve to do so.”

Step Two. Resilience. “A McKinsey Global Institute analysis, based on multiple sources, indicates that the shock to our livelihoods from the economic impact of virus-suppression efforts could be the biggest in nearly a century. In Europe and the United States, this is likely to lead to a decline in economic activity in a single quarter that proves far greater than the loss of income experienced during the Great Depression. In the face of these challenges, resilience is a vital necessity. Near-term issues of cash management for liquidity and solvency are clearly paramount. But soon afterward, businesses will need to act on broader resilience plans as the shock begins to upturn established industry structures, resetting competitive positions forever. Much of the population will experience uncertainty and personal financial stress. Public-, private-, and social-sector leaders will need to make difficult “through cycle” decisions that balance economic and social sustainability, given that social cohesion is already under severe pressure from populism and other challenges that existed pre-coronavirus.”

Step Three. Return. “Returning businesses to operational health after a severe shutdown is extremely challenging, as China is finding even as it slowly returns to work. Most industries will need to reactivate their entire supply chain, even as the differential scale and timing of the impact of coronavirus mean that global supply chains face disruption in multiple geographies. The weakest point in the chain will determine the success or otherwise of a return to rehiring, training, and attaining previous levels of workforce productivity. Leaders must therefore reassess their entire business system and plan for contingent actions in order to return their business to effective production at pace and at scale. Government leaders may face an acutely painful “Sophie’s choice”: mitigating the resurgent risk to lives versus the risk to the population’s health that could follow another sharp economic pullback. Compounding the challenge, winter will bring renewed crisis for many countries. Without a vaccine or effective prophylactic treatment, a rapid return to a rising spread of the virus is a genuine threat. In such a situation, government leaders may face an acutely painful “Sophie’s choice”: mitigating the resurgent risk to lives versus the risk to the population’s health that could follow another sharp economic pullback. Return may therefore require using the hoped-for—but by no means certain—temporary virus “cease-fire” over the Northern Hemisphere’s summer months to expand testing and surveillance capabilities, health-system capacity, and vaccine and treatment development to deal with a second surge. See “Bubbles pop, downturns stop” for more.”

Step Four. Reimagination. “A shock of this scale will create a discontinuous shift in the preferences and expectations of individuals as citizens, as employees, and as consumers. These shifts and their impact on how we live, how we work, and how we use technology will emerge more clearly over the coming weeks and months. Institutions that reinvent themselves to make the most of better insight and foresight, as preferences evolve, will disproportionally succeed. Clearly, the online world of contactless commerce could be bolstered in ways that reshape consumer behavior forever. But other effects could prove even more significant as the pursuit of efficiency gives way to the requirement of resilience—the end of supply-chain globalization, for example, if production and sourcing move closer to the end user. The crisis will reveal not just vulnerabilities but opportunities to improve the performance of businesses. Leaders will need to reconsider which costs are truly fixed versus variable, as the shutting down of huge swaths of production sheds light on what is ultimately required versus nice to have. Decisions about how far to flex operations without loss of efficiency will likewise be informed by the experience of closing down much of global production. Opportunities to push the envelope of technology adoption will be accelerated by rapid learning about what it takes to drive productivity when labor is unavailable. The result: a stronger sense of what makes business more resilient to shocks, more productive, and better able to deliver to customers.

Step Five. Reform. “The world now has a much sharper definition of what constitutes a black-swan event. This shock will likely give way to a desire to restrict some factors that helped make the coronavirus a global challenge, rather than a local issue to be managed. Governments are likely to feel emboldened and supported by their citizens to take a more active role in shaping economic activity. Business leaders need to anticipate popularly supported changes to policies and regulations as society seeks to avoid, mitigate, and preempt a future health crisis of the kind we are experiencing today.

“In most economies, a healthcare system little changed since its creation post–World War II will need to determine how to meet such a rapid surge in patient volume, managing seamlessly across in-person and virtual care. Public-health approaches, in an interconnected and highly mobile world, must rethink the speed and global coordination with which they need to react. Policies on critical healthcare infrastructure, strategic reserves of key supplies, and contingency production facilities for critical medical equipment will all need to be addressed. Managers of the financial system and the economy, having learned from the economically induced failures of the last global financial crisis, must now contend with strengthening the system to withstand acute and global exogenous shocks, such as this pandemic’s impact. Educational institutions will need to consider modernizing to integrate classroom and distance learning. The list goes on.

“The aftermath of the pandemic will also provide an opportunity to learn from a plethora of social innovations and experiments, ranging from working from home to large-scale surveillance. With this will come an understanding of which innovations, if adopted permanently, might provide substantial uplift to economic and social welfare—and which would ultimately inhibit the broader betterment of society, even if helpful in halting or limiting the spread of the virus.”

The coronavirus crisis – a unique opportunity for reflection

Manuel Trajtenberg

[Prof. Manuel Trajtenberg, an economist, is a Harvard graduate, former student of the late Zvi Griliches, and served as Member of Knesset, Israel’s Parliament. This is his ‘take’ on how we can use the COVID-19 crisis to reshape our own perspectives].

At most once in a lifetime we are called upon to confront a dramatic event such as this one, forced upon each of us and upon the entire world. Sure, we are threatened by a rapidly spreading and nasty disease, but there is a good chance that we will be able to avoid contracting it, and if not, that we will be able to recover from it hopefully unharmed. The threat to our health is just part of the story, and not necessarily the major one: the coronavirus has managed to bring to a halt life as we know it, as if we were entering a prolonged “Yom Kippur” regime, just without the prayers and the fasting…

I am convinced that this same menace offers us a sort of respite and thus a tremendous opportunity to gain perspective on our lives, to pause the never-ending rate-race in which we are caught: to succeed in school, to earn a living and build a meaningful career, to find a spouse, build a family and raise children, to care for our relatives, and, oh yes! from time to time also to have a life…

What is this “Perpetuum mobile” for? What are we aiming at? What is truly important and what is superfluous? Do we really need the avalanche of goods and services that we relentlessly strive to acquire and consume, and for which we toil and sacrifice invaluable time, instead of devoting it to ourselves, to our families and friends?

We are about to venture unwittingly into a very different routine, unfamiliar, disconcerting; suddenly we will have much more time on our hands, and probably we will not know what to do with it, lest we “miss out” on something, lest we “waste” it. But then we shall gradually discover that, repressed by the brutal pressures of daily life, there are whole layers and capabilities in our brains that were never given the chance to manifest themselves. In an ironic twist of fate, the coronavirus is about to set these dormant capacities free, and offer them a unique opportunity to act up: the capacity for contemplation, for self-reflection, for meditation, and the ability to take delight in them; the capacity to ponder social interactions and appreciate our surrounding, particularly in observing human nature, so close to us and yet often so remote.

Shame on us if we keep suppressing these dormant capabilities, shame on us if we relate to their surfacing as a “waste of time.” There are those who need to journey to remote Ashrams in India to “find themselves”, far from the madding crowd. Now we have a unique opportunity to go on with our lives, and at the same time open a window on our own inner worlds, only to discover hidden treasures of feelings and insights, that laid there all along hidden from sight by the daily, all devouring routine.

This is not say that it will be not be difficult to deal with the formidable challenges posed by corona, more so at first, let alone if significant hardships arise: economic difficulties, shortages of supplies, uncertainty about disease-like symptoms that may appear,keeping children safely and productively occupied, and so on. All these and further difficulties that we cannot yet envision will surely demand from us a great deal of resourcefulness, creativity, and mental fortitude, and test the limits of our wherewithal.

This crisis is very different from others that we have known in the past, such as the first Gulf War: at that time, we were in daily danger from the threat of missiles and even from a chemical attack for six long weeks, which entailed a total disruption of our daily lives, including rushing often to “safe rooms” and wearing gas masks. But back then it was just us in Israel, not the entire world, and nobody would suggest attaching any positive significance, any silver lining, to a remote war that unfortunately spilled-over to us. Then we simply had to hang-on, to survive, and pray that it would end quickly.

This time 7.5 billion people in virtually every corner on Earth are sharing the same fears, the same disruption of daily life, the same existential questions. This might have been the case as well during the two World Wars of the 20th century, but then again, it is hard to ascribe anything positive to wars, certainly wars of such magnitude of destruction and horror.

Now it is radically different – what looms upon us is not a massive loss of lives and of their material envelop, but a shake-up of the key components of the rat-race that has kept as going for too long: globalization, narrowly defined economic growth and urban crowding. Tough questions and deep doubts hoover about them, and the answers are not bound to come from our political leaders or from the Davos elite. New, fresh answers can spring only from us, provided that we wisely grasp this opportunity, and refrain from treating it as a passing disturbance. It is eminently clear now: the coronavirus is not a “flight by night” occurrence, the disruption of our lives is bound to continue for a long time – as the length of the disruption, so is the magnitude of the opportunity, so is the breadth of the new horizons that may open up to us.

Learning From Taiwan: A Deeper Look [Clue: Democracy & Transparency]

By Shlomo Maital

In previous blogs, I wrote tersely about how Taiwan, Singapore and Hong Kong have excelled in handling the COVID-19 pandemic.

An article in Wired.com gives more details about Taiwan’s success. A brief summary: Democracy and Transparency.

Andrew Leonard writes: “Taiwan Is Beating the Coronavirus. Can the US Do the Same? The island nation’s government is staying ahead of the virus, but don’t ascribe it to “Confucian values.” Credit democracy and transparency. And preparedness (a detailed plan put in place after SARS in 2003).

“AS OF WEDNESDAY, the nation of Taiwan had recorded 100 cases of Covid-19, a remarkably low number given the island’s proximity to China. Some 2.71 million mainland Chinese visited Taiwan in 2019, and as recently as January there were a dozen round trip flights between Wuhan and Taipei every week. But despite its obvious vulnerabilities, Taiwan has managed, so far, to keep well ahead of the infectious curve through a combination of early response, pervasive screening, contact tracing, comprehensive testing, and the adroit use of technology.”

“Taiwan’s self-confidence and collective solidarity trace back to its triumphal self-liberation from its own authoritarian past, its ability to thrive in the shadow of a massive, hostile neighbor that refuses to recognize its right to chart its own path, and its track record of learning from existential threats.”

A BBC report this morning recounts that Taiwan was hit hard by SARS in 2003. In its wake, Taiwan set up stockpiles of medical equipment and detailed contingency plans. The moment China announced the case of a strange type of pneumonia, Taiwan was ready. Incoming flights had passengers tested for fever before they left the plane.

For political reasons, mainland China has vetoed Taiwan’s membership in the World Health Organization. As a result Taiwan has had to prepare for pandemics on its own, without WHO help. That has proved a major boon.

Andrew Leonard continues: “The threat of SARS put Taiwan on high alert for future outbreaks, while the past record of success at meeting such challenges seems to have encouraged the public to accept socially intrusive technological interventions. (Jason Wang, a Stanford clinician who coauthored a report on Taiwan’s containment strategy, also told me via email that the government’s “special powers to integrate data and track people were only allowed during a crisis,” under the provisions of the Communicable Disease Control Act.)”

Leonard continues to describe Taiwan’s transparency: “Taiwan’s commitment to transparency has also been critical. In the United States, the Trump administration ordered federal health authorities to treat high-level discussions on the coronavirus as classified material. In Taiwan, the government has gone to great lengths to keep citizens well informed on every aspect of the outbreak, including daily press conferences and an active presence on social media. Just one example: On March 15, Vice President Chen posted a lengthy analysis of international coronavirus “incidence and mortality rates” on Facebook that racked up 19,000 likes and 3,000 shares in just two days.”

Taiwan, Singapore and Hong Kong are now battling the ‘second wave’ – COVID-19 cases of citizens who contracted it abroad and are now returning home. (Of course nations have to allow their own citizens to re-enter the country). If only Europe and the US would open their windows, much can be learned from how Taiwan handles this ‘second wave’….because, chances are, there will also be a second wave in Europe and the US.

Thanks WIRED for making this freely available!…

https://www.wired.com/story/taiwan-is-beating-the-coronavirus-can-the-us-do-the-same/

COVID-19: Lessons from Three Smart Small Asian Nations Part 3. Taiwan

By Shlomo Maital

Taiwan, officially calling itself the Republic of China, is an island nation of some 23.7 million people, with GDP per capita of some $55,000 (using the adjusted exchange rate, known as Purchasing Power Parity), which reflects Taiwan’s undervalued currency.

Taiwan responded very very quickly to the COVID-19 threat, perhaps faster than anywhere:

“Taiwan acted even faster. Like Hong Kong and Singapore, Taiwan was linked by direct flights to Wuhan, the Chinese city where the virus is believed to have originated. Taiwan’s national health command center, which was set up after SARS killed 37 people, began ordering screenings of passengers from Wuhan in late December even before Beijing admitted that the coronavirus was spreading between humans.”

“Having learned our lesson before from SARS, as soon as the outbreak began, we adopted a whole-of-government approach,” said Joseph Wu, Taiwan’s foreign minister. By the end of January, Taiwan had suspended flights from China, despite the World Health Organization’s advising against it. The government also embraced big data, integrating its national health insurance database with its immigration and customs information to trace potential cases, said Jason Wang, the director of the Center for Policy, Outcomes and Prevention at Stanford University. When coronavirus cases were discovered on the Diamond Princess cruise ship after a stop in Taiwan, text messages were sent to every mobile phone on the island, listing each restaurant, tourist site and destination that the ship’s passengers had visited during their shore leave.”

As of Tuesday, Taiwan had recorded 77 cases of the coronavirus, although critics worry that testing is not widespread enough. Students returned to school in late February.

Speed. Agility. Discipline among the population. Preparedness. Anticipation. “Reading the world map correctly”.

This is what we learn from smart, rich, agile, disciplined small Asian nations.

COVID-19: Lessons from Three Smart Small Asian Nations

Part 2. Hong Kong

By Shlomo Maital

Hong Kong is officially known as “the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China”. It has 7.4 million people and GDP per capita of some $46,000 – higher than that of Israel.

Here, according to the New York Times, is how Hong Kong dealt with the COVID-19 crisis, influenced strongly from its traumatic experience with SARS in 2003:

“ Hong Kong’s heavy death toll from SARS, nearly 300 people, has spurred residents in the semiautonomous Chinese territory to exercise vestigial muscles of disease prevention this time around, even as the local authorities initially dithered on whether to close the border with mainland China. Nearly everyone, it seemed, began squirting hand sanitizer. Malls and offices set up thermal scanners.”

“The most important thing is that Hong Kong people have deep memories of the SARS outbreak,” said Kwok Ka-ki, a lawmaker in Hong Kong who is also a doctor. “Every citizen did their part, including wearing masks and washing their hands and taking necessary precautions, such as avoiding crowded places and gatherings.”

“The Hong Kong government eventually caught up to the public’s caution. Borders were tightened. Civil servants were ordered to work from home, prompting more companies to follow suit. Schools were closed in January, until at least the end of April.”

“On Tuesday, the government of Hong Kong, where only 157 cases have been confirmed, announced a mandatory 14-day quarantine for all travelers from abroad beginning later this week.”

SARS outbreak occurred nearly 17 years ago, in 2003. Despite this, the memory of SARS and the measures adopted at that time are fresh in the minds of Hong Kong citizens. It was the people of Hong Kong who acted, even before the government and administrative officials took action, in the COVID-19 outbreak.

I am certain the same will be true of COVID-19. We will remain this for generations. And hopefully, in the next pandemic, we will act promptly, as Hong Kong did.

COVID-19: Lessons from Three Smart Small Asian Nations Part 1. Singapore

By Shlomo Maital

We can learn a great deal from three small Asian nations or semi-autonomous areas (Hong Kong, Singapore, Taiwan) about how to deal with COVID-19. These lessons are summed up in today’s New York Times, by Hannah Beech:*

Here, Part 1, is how Singapore acted.

I taught MBA students in Singapore, at Nanyang Technological Institute, for many years, and came to know Singapore and its people well.

I can sum up Singapore’s cultural DNA, in place from Day One, in large part thanks to its brilliant founding leader Lee Kwan Yew: We are a small nation, disliked by our huge neighbors. To survive, we must be the very best at everything, and accept no excuses for incompetence.

“Singapore’s strategy of moving rapidly to track down and test suspected cases, provides a model for keeping the epidemic at bay, even if it can’t completely be stamped out completely.

“With detailed detective work, the government’s contact tracers found, among others, a group of avid singers who warbled and expelled respiratory droplets together, spreading the virus…. If you chase the virus, a Ministry of Health official said, you will always be behind the curve.”

Singapore has had a relatively few cases and few deaths, even though the Chinese New Year brought a lot of arrivals from China initially.

The author writes: “Early intervention is the key. So are painstaking tracking, enforced quarantines and meticulous social distancing – all coordinated by a leadership willing to act fast and be transparent.”

Singapore’s key benchmark: To trackers seeking where the COVID-19 was contracted, for those testing positive — you have two hours to bring us concrete answers. Two hours. No excuses.

In Singapore, “details of where patients live, work and play are released quickly online, allowing others to protect themselves.”

Violation of privacy? Embarrassing? Of course. But public health comes first. And a disciplined population accepts this.

[Important correction: My friend Bilahari Kausikan, former senior Foreign Ministry official in Singapore, writes: NYT story was misleading in one detail: it gives the impression that we release the names of the infected. We don’t do that but refer to them by case number. The details are of date, time and places they have visited so that you can be alerted and if you have been there at the material time and date, get yourself checked.”]

Western nations seem to be chasing the virus, after it has arrived, rather than acting pre-emptively well before it unpacks its bags and settles in.

Perhaps next time, we will follow Singapore’s lead?

- “Asian hubs offer model for tackling an epidemic”. New York Times March 19/2020

COVID-19: Why Do More Men Die Than Women?

By Shlomo Maital

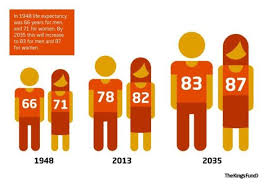

Women live longer than men. It’s true. Here are the facts, from the World Health Organization:

In 2019, more than 141 million children will be born: 73 million boys and 68 million girls.

Based on recent mortality risks the boys will live, on average, 69.8 years and the girls 74.2 years – a difference of 4.4 years.

Life expectancy at age 60 years is also greater for women than men: 21.9 versus 19.0 years.

Women have a longer life expectancy than men at all ages.

Many years ago, when I studied demography at Princeton (at Ansley Coale’s famed Office of Population Research), this fact was true even then – and I read a study of monks and friars, in a monastery, whose life expectancy reflected the same advantage for women – so, it is not environmental factors that cause it.

In fact, we’re not really sure why women live longer. There are many theories.

And now, comes COVID-19. Writing in the daily Haaretz, Asaf Ronal observes that the mortality rate from COVID-19 for men is 2.8%, while the mortality rate for women is 1.7%. That is a massive difference. This is adjusted for age, and other factors.

Why?

There are theories. Behavioral: Men are ‘heroes’ and seek medical care less than women. Physiological: Female hormones protect them. Immunological: Female immune systems work better. Biological: the ‘receptors’ viruses like to invade on human cells reside in part in Chromosome X, women have two copies of it, thus they are more susceptible, so their immune systems are more alert and wary to attack invaders.

These are all theories. None have really been fully tested.

And finally, my own observation: As we observe spatial separation here in Israel, and as I watch both men and women experts explain things and advise us on TV – again, as always, I am struck by how much better women are at delivering information, credibly, authentically, than men, given the same level of expertise and training.

If only the men would leave it to the women – and just shut up. US President, are you listening? And Israeli PM? Men — take care of yourselves. Let the women run things. They do it better.